Restaurant Review: Yan Dining Room – A Compelling Tasting Menu in Toronto is Hiding in Chinatown

I arrived at Yan Dining Room with the kind of mild skepticism reserved for restaurants that describe themselves as “experiences.” The word has been stretched so thin in contemporary dining that it now often means little more than a fixed price, a dim room, and a sequence of plates delivered at a glacial pace. What I did not expect, tucked behind the familiar clatter of Hong Shing in Chinatown, was something closer to a private banquet disguised as a restaurant.

Yan Dining Room is hidden in plain sight. You walk through Hong Shing’s busy front room, past the woks and steam and fluorescent glow, and slip into a smaller, darker space at the back – much like a speakeasy. The transformation is immediate. The noise dulls. The lighting softens. No more than 15 small tables are set with crisp linens, chopsticks, and small name cards that announce each guest’s place like a dinner party assignment.

The word “yan” means banquet, and that translation is not decorative. The meal borrows its structure, its spirit, and its emotional logic from Chinese celebratory dining, where food is not just sustenance but language, a way of expressing care, memory, and continuity. At the center of this philosophy is chef Eva Chin, whose cooking draws heavily from Cantonese traditions. Her food is nostalgic without being backward-looking.

Chin doesn’t hide in the kitchen. Several times throughout the evening, she steps into the room to introduce a dish, explain an idea, or tell a short story. These moments never feel rehearsed. They feel conversational, sometimes slightly rambling, occasionally funny, always sincere. If many tasting menus try to impress you with technical wizardry, Yan tries something riskier: it asks you to care.

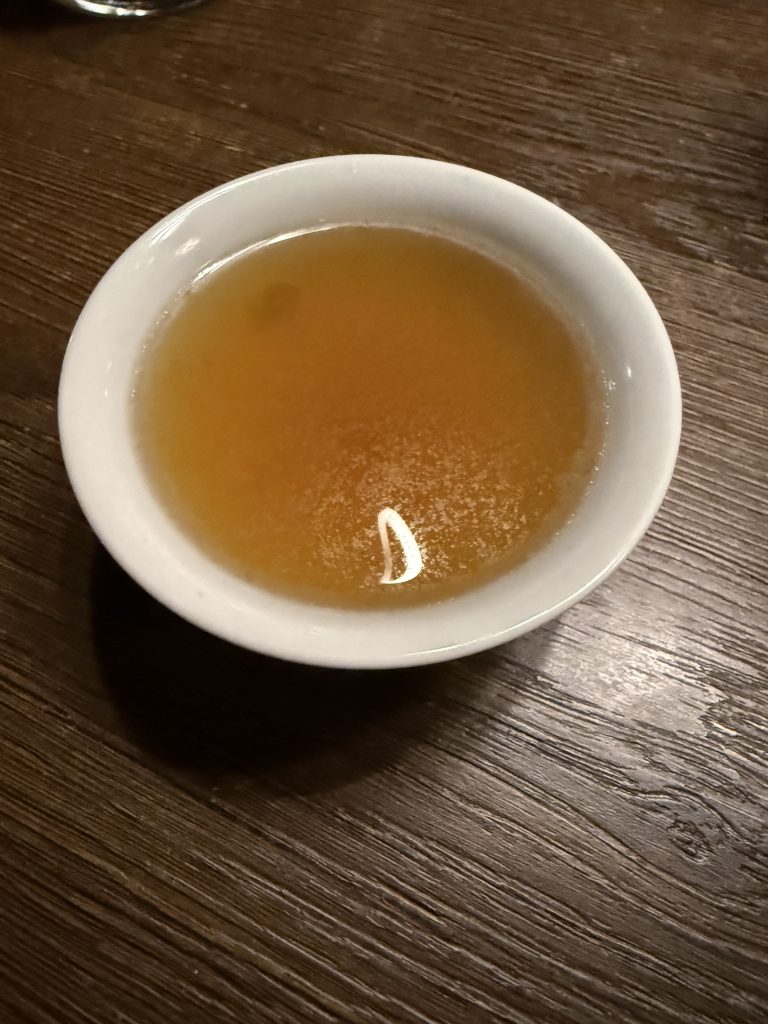

The meal begins gently, as most good stories do. A clear broth arrives first, made from mature duck and pear. It is pale, fragrant, and quietly restorative, the kind of soup that seems designed to slow your breathing. The pear lends a faint sweetness; the duck adds depth without heaviness. It tastes like patience. If this were all that was served, I would already feel looked after.

Small snacks follow, a constellation of compact, concentrated flavours. An oyster shot dressed in Chaoshan-style seasoning lands somewhere between briny and gently funky. A croquette flavored with fermented bean curd delivers a creamy interior that blooms into savory richness. Cured ham, hongshao carrots, and other bite-sized offerings flicker across the table like opening credits, introducing themes that will reappear later: fermentation, preservation, sweetness balanced by salt, the pleasure of restraint.

One of the first dishes to truly announce Yan’s ambitions is called Hundred Flower Radish. It arrives looking almost austere: a pristine white cylinder resting in a shallow bowl. Only after the server pours a warm broth around it does the perfume rise…dried shrimp, ginger, a whisper of the sea.

The radish has been hollowed and stuffed with a delicate mixture of sidestripe shrimp and dried seafood, then braised until yielding but not collapsing. The name references the Cantonese idea of “hundred flowers,” shorthand for complexity hidden beneath simplicity. Each spoonful reveals layers: the radish’s mild sweetness, the briny chew of shrimp, the silky broth tying everything together. It calls to mind turnip cake from dim sum, but refracted through a fine-dining lens. Familiar, but transformed.

Chin introduces the next dish, “Mom’s Dumplings”, by talking about learning to fold dumplings in her family kitchen, about watching her mother shape each pleat with care. The dumplings arrive plump and steaming, filled with pork belly and winter cabbage.

The filling is rich, juicy, and deeply savory, the cabbage offering gentle sweetness and crunch. A touch of black vinegar and chili oil on the side adds brightness and heat. Eating them feels grounding. In a menu that travels through memory and reinvention, this dish plants its feet firmly in the present: this is who I am, this is where I come from, this is what I love.

The room grows progressively louder as the night unfolds. Wine glasses clink. Strangers lean toward one another to compare impressions. The space helps dissolve boundaries and bring people together through food.

And yet, when Chin steps forward to speak, the noise falls away.

Eight Treasure Duck is the evening’s centerpiece, inspired by a traditional banquet dish in which a whole duck is stuffed with glutinous rice, chestnuts, lotus seeds, and other auspicious ingredients. Chin’s version arrives deconstructed but no less celebratory: a slice of tender duck with crisped skin, resting atop sticky rice studded with chestnuts and dried fruits, bathed in a glossy, aromatic sauce.

The flavours are lush but controlled. The duck is deeply savory, the rice faintly sweet, the sauce gently spiced with star anise and citrus peel. It tastes like something you would remember long after forgetting the name of the restaurant where you ate it.

Dessert arrives disguised as a joke. Lo Bak Go is Cantonese for turnip cake, the savory dim sum staple. Chin’s version looks similar — a neat, pan-seared square with a golden crust — but it is made from heirloom carrots and finished with nai lao, a fermented milk custard. The interior is soft, lightly sweet, and warmly spiced. The crust offers a gentle crunch. The nai lao adds tang and creaminess.

It is playful without being silly. It feels earned. It closes the meal by looping back to where it began: tradition, reinterpreted.

Service matches the tone of Yan Dining Room. Chin’s partner in business and in life, Theresa “Tree” Walsh, heads up front of house, and does it well. The team of servers are relaxed, and attentive without hovering. Tea is refilled before you realize your cup is empty. Plates arrive at a steady rhythm. Nothing feels rushed, but nothing drags. There is a sense that everyone in the room is working toward the same goal: to make you feel welcome.

What ultimately distinguishes Yan Dining Room is not just the quality of the cooking, though the cooking is very good. It is the emotional clarity of the project. Chin is not trying to prove that Chinese food belongs in fine dining. She assumes it does. She is not interested in spectacle for its own sake. She is interested in memory, in continuity, in showing how a cuisine evolves when carried by people who love it enough to question it. The storytelling is the backbone.

By the end of the night, I did not feel dazzled so much as gently rearranged. I felt fuller than when I arrived, yes, but also strangely calmer. I had eaten well. I had listened. I had been included.

In a city where diners have every restaurant option to experience, Yan Dining Room offers something rarer: sincerity, expressed through food that knows exactly why it exists.

That, more than any technique or trend, is what makes this place worth seeking out.

Bisous,

Mme M. xoxo

4/5 étoiles

La rubrique de Madame Marie

1 étoile – Run. Before you get the runs.

2 étoiles – Mediocre, but nothing you couldn’t make at home.

3 étoiles – C’est bon, with some standout qualities.

4 étoiles – Many memorable qualities and excellent execution. Compliments to the chef.

5 étoiles – Formidable! Michelin Star quality. Book a reservation immediately.